BEAUTIFUL CREATURES (I)

Much like bumping into Brigitte Bardot in the supermarket, the first time I saw his work, I was lost forever. It wasn’t in the slightest bit like when people flock to see Mona Lisa because it’s the most famous painting in existence either. Rather, it was a small piece of wood, four inches by two inches with the print glued onto it that hung in our kitchen forever. I say ‘hung’ but it was stuck to the wall with double sided tape.

It’s not even his best work. It’s a simple picture of a crow in a tree with a stocking. For the longest time I had no idea who drew it and truth be told, when you’re a kid, you could care less that it was even created by someone. It’s not how you think at that age. But as the years got behind me two and two began to equal four and I joined the dots together for myself.

Peter Pan in Kensington 1912 - Quietly filling stocking

I asked my mother about it. Where did you get it? Did somebody give it to you? Tumbleweed. She can’t remember anything aside from she bought it because she liked it and frankly, that’s really about as good as anything can get when you’re an artist.

This is how Arthur Rackham became my favourite artist of all time, by a chance sequence of events that flowed down to me. Don’t you think it’s odd, that in reality, it could have been anything. Take your pick - millions of prints are sold every day around the world. If she’d picked up something by Dali, maybe he would be my main man. Who knows.

I like to think this was intended for me in the house and me alone. Everybody else ignored it like it was inconsequential as a light switch. I was the only one who would stand there wondering what the crow was trying to tell me.

See, Rackham didn’t feel like ‘just’ an illustrator in the friendly, decorative sense to me. His drawings didn’t arrive smiling despite the grins on the creatures he drew. They’re more like reliable witness statements from the other side of the curtain. The images seem less interested in impressing you than bringing the news that while you’re not looking properly, faeries are indeed having a snowball fight with errant pixies and if you can’t see it too, that’s far from being their problem with the world.

When I finally got around to some proper research, I discovered my little wooden block featuring a crow and a stocking is from Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens - which actually depicts the character Solomon, the wise crow of the Gardens, preparing for retirement by stashing items in a stocking on a yew-stump. For some reason, this made me happier than it should have. A scene from a book about a boy who never grew up hung right there in the kitchen for a boy who would also never really grow up. What’s not to love about that?

I do not share a birthday with Rackham. Fact of the matter is, we have nothing in common at all, or so I thought. He was born in 1867. I was born exactly 100 years later - give or take a couple of months - and cannot draw to save my life or the lives of my children. As a young man, he worked in an insurance office and studied art at night...

Let’s pause for a second because it’s hard to imagine a world with no distractions. No box of entertainment of any kind that plugged into the wall to suck your time. There was you, making money somehow or you would starve to death in the blink of an eye, going outside or staying inside. Those were probably all the options you had available but both options are dense in the extreme and sure as eggs are eggs, there’s no empty calories kicking around. Nobody is stopping at Starbucks on their way to the park. The biggest thing you were going to be hearing outside was probably the sound of silence.

From my admittedly scant research of the era (which does actually amount to more than watching a few Basil Rathbone Holmes movies), it seems that those of an artistic bent were bored beyond their wildest dreams and the only escape is to learn how to use it. Without the distraction of the next episode of Game of Thrones or Coronation Street, people got things done.

By the late 1890s, Rackham was illustrating books for adults as much as children, which is a crucial point really, that’s often forgotten. Fairy tales weren’t yet locked into the nursery. They were still strange, moral, occasionally cruel and very much a part of adult life.

Maybe they still are.

The turning point came in 1905, (he’s heading for forty at this point) with his illustrated edition of Rip Van Winkle. This is where everything clicks into place and his soul (which has been out wandering, gathering evidence for the future) returns to him fully loaded. The trees become characters. The landscape stops behaving. The figures begin to feel more like temporary visitors in a world that existed long before them and will continue long after.

Rip Van Winkle 1905 - Sleep of Rip

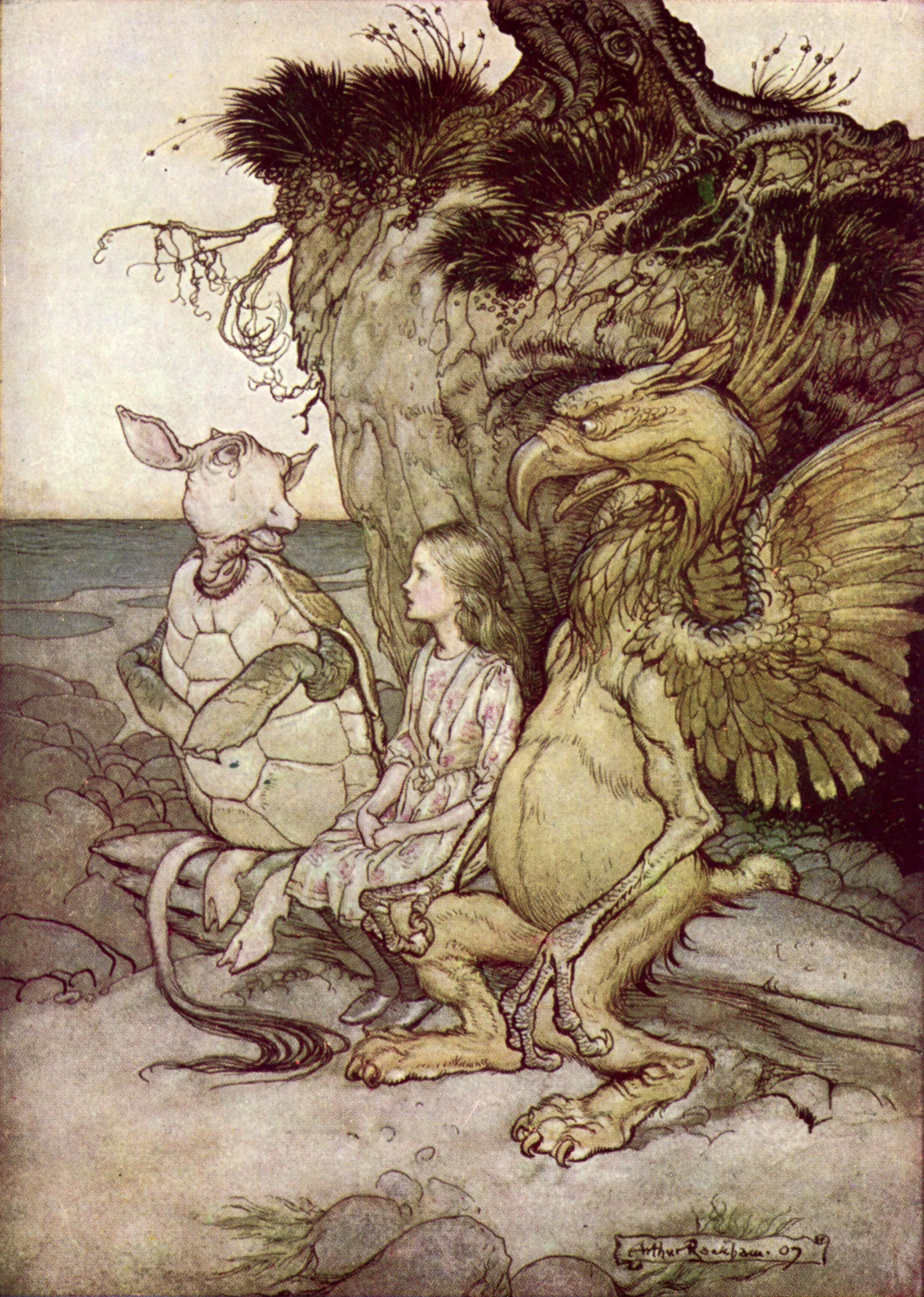

You can see it in the work that follows chronologically: Rip Van Winkle leads to Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906) and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1907). Each piece is more than a simple drawing. You could almost throw the words away with the illustrations working as hard as they are.

I believe (and others may too but I’ve never read his life story for fear of spoiling what I think I know) that he was working in fantasy to escape, using it to put forward some uncomfortable truths because that’s were they’re allowed to live and go unquestioned by folk who aren’t looking properly.

Look closely at some of the work and you’ll find small, wiry figures almost ill-equipped to survive the landscape. Has he put himself in here? He was certainly no Bruce Lee. The world mirrors ours but it’s simply not the same. It’s different, humorous, sardonic perhaps.

The crowning glory of this subterfuge is that he worked in gift books. Expensive books bought as Christmas present. Sneaking a magic trick like this into the homes of the elite is a mark of true rebel punk. If I twist it hard enough, it’s like an episode of Supernatural, because yes, eventually these stories ended up in the nurseries of an entire nation.

That’s the trick - and for a man who looked scared of his own shadow (maybe rightly so), he didn’t back down from a challenge. By the time Rackham came to Alice, the pictures were already spoken for.

John Tenniel had got there first and had done such a thorough job, that his drawings had effectively fused themselves to the book. They weren’t illustrations anymore — they were memory. You didn’t picture Alice when you read it; you remembered Tenniel.

Many illustrators would have backed away at that point and found something else to work on. Or worse, tried to soften their hand, tiptoe around it, maybe sneak in under the radar with something polite and inoffensive.

Rackham didn’t flinch.

He went straight at it. Same book with the same words and crucially, he didn’t try to redraw Tenniel’s Alice. He didn’t argue with it or apologise for disagreeing with it either. He simply saw the book differently and trusted that his talent.

His Alice is thinner, stranger, more alert. The world around her feels less like a stage set and more like something that might shift if you stopped watching it. The background matters. The air matters. Things loom. Things wait.

This is what I see when I study his work.

Alice's Adventures in W'land 1907 - Gryphon & Mock Turtle

It’s not bravado — it’s nerve. The nerve to say: this book can survive another way of looking at it. That images aren’t answers, they’re interpretations. That there isn’t a single correct version burned into stone because Walt wouldn’t get to work on it for close on another fifty years... and then it really was over.

Looking back to when I first dug up his early work and studied it in context, that was probably the first time I understood that tradition isn’t something you have to overthrow.

If you see clearly enough, you can stand next to it and become part of the landscape as well.

An important part of the jigsaw puzzle here is how he worked. Rackham drew in ink first and colour second, which meant the bones were always visible through the watercolour that was his secret weapon.

Watercolour is painting with tinted water (natch). It’s a natural element and even though it’s long since dried on Rackham’s watch, it retains its watery quality for me, almost allowing the picture to still move if you look at it from the corner of your eye.

I heard it said once - I don’t think I said it but I might have - that if you understand the trees in his work, you understand Rackham. His trees are never really just trees. They work hard whenever they appear. Before Rackham, trees existed in illustration to fill space, indicate outdoors and behave politely. Rackham took a chainsaw to that idea. In his work, they hunch over what other characters are doing, they wait and watch - they’re practically static humans. Look closely and you’ll find they have elbows, knuckles, spines...

The ink line loops, doubles back, hesitates, tightens. It behaves the way an ageing body behaves. The trees might look tired, but never weak. Between the branches, Rackham leaves pockets of white space that often resemble faces or suggest eyes. He doesn’t draw monsters in the trees as such, but he did figure out a way to let your brain do that work for him.

Wonder Book 1922 - The Hawthorne Tree

I was late when I came to this discovery but all of that infiltration of posh houses must surely have disturbed more than a few children who spent their evenings before bed poring over the books.

When you’ve done something for long enough, there simply comes a time when you know what you’re doing. I suspect Alice cemented it for Rackham because next, he returned to the Grimm fairy tales. No longer having to prove himself to the world, he sets himself free in a much darker way. Magic is no longer as kind as it was. Everything is a little more menacing but he manages to build it for two different sets of eyes. Adult eyes see the literal interpretation. A child’s eyes however will linger. That axe really is buried into that anvil trapping the old man in the process. It’s a fine line to walk but he pulls it off time after time.

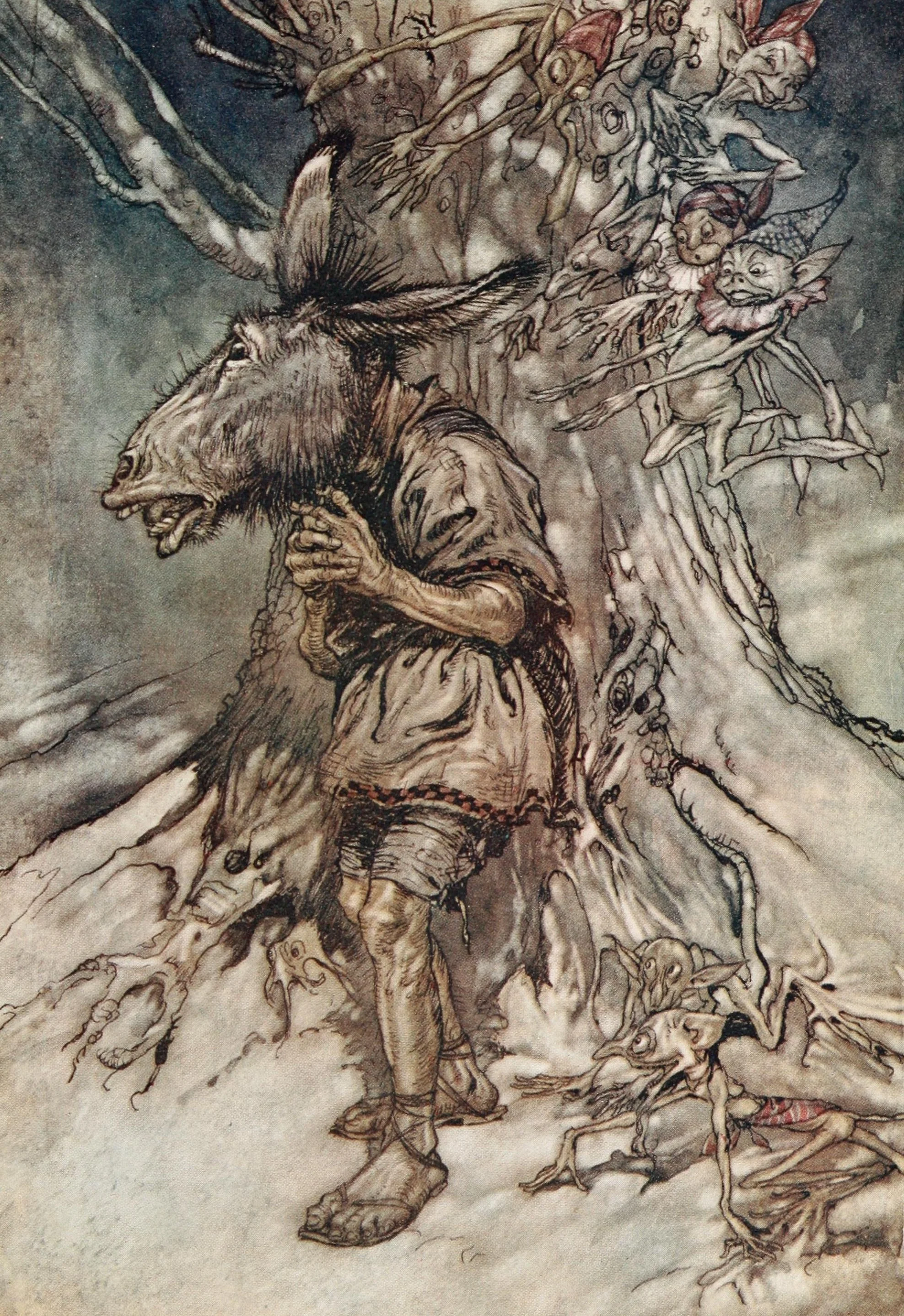

And while Grimm is fine for somebody like me in the modern world, it’s perhaps his next commission that cements him into the hierarchy of illustrators: Shakespeare’s Midsummer Nights Dream. The ultimate story of fairy madness sure had a lot of source material from which he could build more wicked and mischievous woodland folk - and this is exactly what he did. Look closely and see how their faces have changed from earlier versions. He’s almost redefining how they are allowed to be in literature.

Before Rackham, fairies in art tended to be on the pretty side. Small, winged, child-like even. Riffs on cherubs if you will. But that’s not how fairies in literature had always been. Pre-Victorian fairies stole children, messed with your livestock, punished curiosity and absolutely had their own logic. Rackham appears to take these ideas and fuses them together to produce fey that appear to be almost beaurocratic. You can practically see the rules they have to live by dripping from the page.

I know nothing about Shakespeare because I don’t like him much but if you dig around, you’ll find this is not a play about whimsy (which is often how it comes across), but is actually about control, manipulation, and power disguised as play. There’s nothing Disney-esque about any of this. Sometimes his creatures are barely distinguishable from leaves as they blend into bark and shadow or appear in clusters rather than as individuals. The smiles are gone to be replaced with smirks one step removed from malice. They’re not evil but neither are they interested in the world outside of that of Fairy - an idea better encapsulated by Tolkien perhaps?

Midsummer Night's Dream 1908 - Bottom will sing

I sit here at the kitchen table with Solomon looking down on me, albeit from an entirely different kitchen, looking at his output after this period. Rackham seems to change and I kind of know how he feels. It doesn’t take your whole life to say all the things you have to say. His stall has been laid out. Everybody knows what he can do. He moves into a period of consolidation. He’s always improving but it’s within the world he’s already built for himself in some bizarre twist on art imitating life imitating art.

In the years that followed, he simply kept drawing worlds where humans were temporary, forests were older than memory, and magic wasn’t obliged to explain itself. The line grew quieter, the images more restrained even, but the temperament never changed. He trusted that once you’d learned how to see what he wanted you to see, you wouldn’t forget. There was a beautiful version of The Tempest, followed by one of my favourites, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, which featured some fantastic colour work and the trees! Oh the trees...

Time, as it loves to do with alarming regularity, changed his world. With hindsight, we have come to know the Golden Age of Illustration as being from somewhere around 1890-1914. It’s inevitable perhaps that the First World War made a mess of things. That Golden Age consisted of expensive gift books, limited print runs, illustrations as an actual selling point, middle-class security even. You bought the book because of the illustrations much like I used to buy albums because of the covers.

By the time the war was over, the model was all but dead. The technology might have improved but with it came brutality with the presses favouring bold shapes over anything with fine lines and while they didn’t destroy his work, they weren’t exactly kind to it either. The printing industry was learning how to rush but that’s not the world Arthur Rackham lived in.

And yes, here comes the chopper to chop off your head. We’ve seen it a thousand times by now: here comes the moving image and visual storytelling is no longer static. Rackham’s work lived in stillness and subliminal suggestion — qualities that don’t tally with a world discovering motion. The industry changed around him, not because he was outdated but because it no longer had the patience for what he was offering.

This is how all things fade into the past. By the 1920s, Rackham is still only in his fifties. In 1923, the Walt Disney studio is founded and Snow White is released just two years after Rackham dies in 1939.

I’m a big fan of Disney but writing from this aspect, I can see how the animation studio took away the good stuff. Whereas we were once trusted to interpret an image correctly, Disney took the model and, as is the American way, over-explained it. Everything gets emotionally signposted, morally simplified and is endlessly repeatable. Throw in a song or two from a singing animal and there’s nothing left for the viewer to do except sit in their chair with a bag of snacks, letting the magic wash over them.

Childhood is now being protected and fear is something to be removed. Fantasy is now. something to comfort the masses and this is not Rackham’s way at all.

And yet here he is right in front of my eyes.

A crow with a stocking, stuck to a kitchen wall with double-sided tape again, quietly ignoring every advance that visual culture has made since 1906. He doesn’t move. He doesn’t sing. He doesn’t explain himself. He just watches and I have no idea what he’s stashed in his stocking.

I’ve lived through the age of the advancement of moving pictures to the point that dinosaurs are now real and I can make a film myself with the thing in my pocket. Streaming platforms rule the airwaves 24/7, infinite choice and infinite distraction is infinitely everywhere and everybody has an opinion about everything, but somehow I’ve ended up back where I started with a 4x2” block of wood.

I don’t think Rackham would have had much to say about the world that followed him. He wasn’t interested in keeping up.

He’d already finished his sentence.

Peter Pan in Kensington 1912 - Away he flew