Who Can Fix The Doctor?

I can. Well, actually I can’t but I know exactly how to and it’s not that hard.

Remember when Doctor Who was actually scary–or if you’d grown older, at least worth watching to keep up with your inner ten year old? I’m not talking about the CGI space jellyfish or the cheap jump-scares that pass for threats these days. I mean properly, fundamentally, ‘back away a few feet’ scary. There was something about those old rubber-and-glue monsters, the ones you could probably smell if you were in the room, that just worked. They had weight, texture and presence. You might have laughed at a wobbly Dalek or a dodgy Sea Devil, but at least you believed they were there with you, not rendered into the episode by a guy called Steve in his pyjamas at 3 a.m.

Right now, Doctor Who monsters look like they’ve wandered in from a rejected PlayStation game and the pay-off for embracing the ‘latest technology’ is that nobody cares whether they get blown up, zapped, or inevitably ‘redeemed’ with a ten-second speech about hope and friendship. Nobody is worried by pixels. If you want to save Doctor Who, you don’t need a new showrunner, a fresh gender for the Doctor, or even a bigger BBC budget. You need to drag the monsters back into reality. You need to let the weirdness sweat again. You need to treat the audience with some respect for knowing what a story looks like.

And—here’s the radical part—you simply need to do less, not more. Less digital sleight of hand, fewer over-crowded casts (that’ll save you a few pennies), and more stories where we actually care who’s on screen, what’s chasing them, and why the hell it’s all happening. We don’t need another Time War. We need stories with heart, monsters with souls (and maybe a bit of drool), and villains who could actually stand behind you at a bus stop and make you wet yourself because that’s the way stories work. It’s been the human psyche for millennia–you can’t change it now because a bunch of suits around a table think they know best, because they don’t.

So here’s how you fix Doctor Who: tear up the green screen, raid the foam latex and call in the creature shops, because the future of the show is hiding (in the past) in plain sight.

THE SLOW DEATH OF WONDER

It’s not the only show/franchise that’s guilty, but it’s the only one I care about. There’s a dirty secret about modern sci-fi TV: the more money you throw at CGI, the less anyone remembers your monsters. Think about it. Nobody is putting a Weeping Angel tattoo on their arm because the CGI was top-drawer (and believe me, I’ve seen a few). The scariest moments of Doctor Who have always come from stuff that was physically there—actors in rubber suits, plastic mannequins with guns in their hands, or a Dalek rolling after Tom Baker at an uncomfortably fast speed because it was so claustrophobic.

CGI should have been a gift to Doctor Who—a license to finally do all those stories that were too big for the budget. Instead, it’s become a digital crutch. Almost every new villain in recent years has been a slick, pixelated, weightless thing you could walk through if you were on set. The actors are told to “look scared,” but how are you supposed to react to a tennis ball on a stick, or worse, an X on a wall for the effects team to draw over later? It’s not a good day at the office for the actors. There’s nothing memorable for them to take home or get excited about when promoting the show–it’s simply boring.

The big thing that nobody wants to say is: it’s not just nostalgia talking. It’s science. Our brains know the difference between real and fake and no matter how high-res the rendering, you can tell the difference when you’re walking past the TV to make a mug of coffee. That’s why those classic monsters stick in the mind decades later. They shouldn’t have worked, but somehow, they did.

The show’s own history backs this up. Tom Baker’s Doctor squaring off against the Zygons? Legitimately unnerving. Christopher Eccleston staring down a room of plastic mannequins? A classic reboot. This last few years all I can promise you about the show is that there are a hundred school kids rolling their eyes and checking TikTok because a guy dancing in his pants inside a gorilla costume is more entertaining. Mark this on your soul: If it’s not in the room, it’s not in the memory.

Den of Geek nailed it: “CGI monsters are less scary because you can’t ever imagine them lurking in your closet. There’s no ‘what if?’ Only ‘that’s cool, I guess.’” Spot on. Doctor Who needs to find its ‘what if?’ again. Ain’t nobody in the world going to be making a costume of recent monsters to go to school in, but a Dalek? That’s very achievable, if not actually a lot of cardboard and hard work.

BRING ON THE MONSTER MAKERS

Let’s get one thing clear: this isn’t just an old-man’s plea for the good old days. Some of the greatest, strangest, and most unforgettable screen monsters of the last two decades have been hand-built, puppeteered, and sweated into existence by people who actually know what they’re doing.

Take Guillermo del Toro—king of the monsters, kids. Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water and the forthcoming Frankenstein… these aren’t just cult classics because of their stories. It’s the monsters. Doug Jones spent hours each day sweating into a faun suit, blinking through two-inch prosthetic eyelids, moving like something you’d see in a fever dream. The Pale Man—eyeballs in his hands, twitching fingers, skin like stretched parchment. No CGI in sight. Just actors and artists, turning nightmares into something tangible. I know nothing about the dark art of budgeting but I am absolutely certain of the difference in saving your show and creating a legacy that’s not dribbling through your fingers like sand.

Same goes for The Shape of Water’s Amphibian Man. Doug Jones (again) spent hours in the makeup chair, but the result is a creature that’s actually there, emoting, reacting, kissing the lead. del Toro has said it a million times: “I always want a real performance inside a monster.” If you want a recent-ish example of how it’s done, take a look at del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities on Netflix. It’s a series that embraces practical effects and lets its monsters get under your skin the old-fashioned way.

It’s not just about budget—it’s about presence, texture, and the sense that, in the right light, you might actually run into this thing on the street.

We are not at the mercy of Disney either. Want homegrown examples? Look at Henson’s Creature Shop which is still running and still brilliant. They made The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth, and most recently, the astonishing puppetry in Netflix’s Age of Resistance. Those creatures will outlive most CGI in the cultural memory by a country mile. These are things that will find their way to being tattooed on skin. That’s always my ‘go to’ for how important something is in pop-culture.

Don’t believe it? Look at the Demogorgon from Stranger Things. Spectral Motion built a suit, not just a wireframe. The Mandalorian’s Grogu/Baby Yoda? A puppet. These are modern classics because you could pick them up, hug them—or be eaten by them, but most importantly, we can relate to them as being sentient beings.

Doctor Who should be raiding these workshops, not dialling up a render farm in Vancouver. I did some actual research: you can build a world-class monster suit for around what you’d spend animating one big CGI set piece—and the suit is yours for the rest of the series. Every time you roll cameras, it gets cheaper. With CGI, you pay every time, and you’re stuck in a queue waiting on that aforementioned render farm. Want that in numbers? A practical suit might be £40–80k up front, but use it for years. CGI: £40–200k for a single big scene, then pay again every time you need more.

The best monsters—the ones that haunt you or inspire you or just stick in your head like an itch—aren’t just well-designed, they’re part of the world. They breathe the same air as the actors. They sweat under hot studio lights. If you tried to shake their hand, you’d actually touch something. That physicality isn’t a nostalgia trip—it’s a psychological shortcut straight to the fear-center of your brain.

It’s the difference between a ghost story told around a fire and a chain email about Slender Man.

One is present, the other is just pixels on a screen. It’s that simple.

ALL THE TIME, LESS IS MORE

Here’s where Doctor Who’s gotten lazy—and yes, I’m talking to you, BBC/DISNEY–whichever of you is responsible. Not every episode needs to pack in a dozen new characters to make sure you ticked your diversity boxes, three planets, four time jumps, and a monster you’ll forget before the credits roll. Some of the best TV in history has one monster, a handful of characters, and the time to make you care–and most of that “best TV in history” was actually Doctor Who.

Think Blink. One monster. Four people. A simple idea, executed perfectly. The Weeping Angels (practical effect, not CGI) instantly became iconic—not because the effects were flashy, but because the story let the threat breathe.

You don’t have to have a new alien every ten minutes to keep an audience’s attention. You need to slow down because people, no matter how old, appreciate a good story. We are nothing but stories! Give us one story, one group of people, one good monster, and let us actually be concerned about what’s going to happen. You want the audience to care about your monsters? Spend less time designing them on a MacBook and more time letting them do something.

THE CASE FOR CHARACTER OVER PLOT DEVICE

The other thing Doctor Who forgot somewhere after the Capaldi era, is that monsters aren’t just there to look scary. The best monsters have motivations. They have personalities, quirks, heartbreak, sometimes even a twisted sense of humour. When all you get is a shiny CG blob with a tragic backstory crammed into two minutes of exposition, you get “monster of the week” syndrome—and that’s what’s killing the show.

Look back: the Daleks were more than just tin cans with plungers. They had a philosophy. The Cybermen were a tragic warning about what happens if you sacrifice too much for progress. Even the Autons, plastic shop window dummies, had a weird, sinister poetry about them.

Take a look at Madame Vastra and Strax. Those episodes were beautiful - Vastra (played by the amazing Neve McIntosh) in particular. If you ever needed to point at a character in costume as being real, that’s the one. She is as real as any other character in any show. She has a reason to be, a backstory... and a life that we’re allowed to get glimpses of with her constant companion, Jenny. That’s exactly how you make creatures work within the context of the show, so we know it’s not an ‘alien theme’ to anybody because it’s been done before. (On which note, where was the Vastra spin-off we desperately wanted? It’s still not too late!)

Or take my personal favourite, the Judoon, giant space rhinos in full rubber suits, stomping down hospital corridors and bellowing in untranslated grunts. They’re as real and unforgettable as any classic monster, not because of CGI wizardry but because someone actually put in the work to make them exist. The Ood, too: creepy, sympathetic, fully realised, and not just because of their tentacle faces but because they feel present—part of the world, not layered on top of it.

Compare that to modern Who villains. Do you remember the ‘Skithra’? The ‘Stenza’? Of course you don’t. They’re made to be forgotten—because they were never really there in the first place. Even their names appear to be computer generated rather than chewed over by a concerned writer with a pencil who can’t sleep because the right name is always just out of reach. It makes a difference and it makes a difference because it’s important.

And I’ll make a case for being against overstuffed casts too. Doctor Who is not the only guilty party. Take a look at Marvel’s Eternals. There are so many characters in it, none of them got much of a story and nobody had a chance to be cared about. Remember any of their names? Me neither. That’s the risk when you treat your cast like a census. If everyone is just there to deliver a plot point, you might as well put a green ping-pong ball on a stick and call it Cousin Steve. (Actually, that’s how they make half the monsters now. See the problem?)

Compare this to Peter Capaldi and his monologue episode. Worlds apart in every way.

HOW THE DOCTOR CAN LEAD THE PRACTICAL REVOLUTION

Doctor Who should be the show that dares to look different. The show all other shows want to be. It always has been, at its best—rough around the edges, always a few steps outside what the big American shows are doing. But lately, it’s felt like Who is chasing Netflix, instead of setting the tone for future generations to want to be involved.

Leaders don’t chase, they wander off and do their own thing

Here’s how you fix it:

• Commit to practical monsters for an entire season. Not just a token one-off. Build the whole vibe around it.

• Hire artists, puppeteers, creature designers from the likes of Henson, Weta, Spectral Motion–and those are just the first names on my list. Hell, there’s a hundred indie FX shops in the UK alone who could use the work. Let them go wild.

• Give the monsters proper screen time. Not “blink and you miss it.” Build a whole arc around one or two. Make them characters, not plot delivery systems. They need a reason to exist. Those pesky Sontarans had a clear goal not a random reason to turn up.

• Let the actors act with them. Let the directors frame shots that aren’t just “we’ll fix it in post production.” Give your Director of Photography something to light before there aren’t any left! (The DP is the one who can make a practical monster look terrifying, mysterious, or just plain weird—because they’re not stuck having to ‘fix it in post’. Give them something real to point a camera at, and they’ll make it sing (or howl, or drool, as required) without them ever saying a word.

• Slow the stories down and let the weirdness breathe. Even six year olds can handle it and if they can’t, there are plenty of other shows they can watch that deliver exactly that.

And please don’t say it can’t be done on a TV budget. The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance did it. Stranger Things does it. Even The Mandalorian, a Disney juggernaut, insists on practical effects for its most beloved characters–and when it didn’t, it really suffered.

The only thing stopping Doctor Who coming back with a vengeance is a lack of nerve.

And that’s unforgivable.

HERE’S WHAT THERE IS TO GAIN—AND WHY IT MATTERS

If Doctor Who binned the CGI crutch and went all-in on practical creatures, we’d get something we haven’t seen in years: stakes! Suddenly, monsters would have gravity—literally and emotionally. You’d see the sweat on a performer’s brow under the mask. The actors would have something to act with, not just stare past, hoping the VFX guy gets their eye-line right.

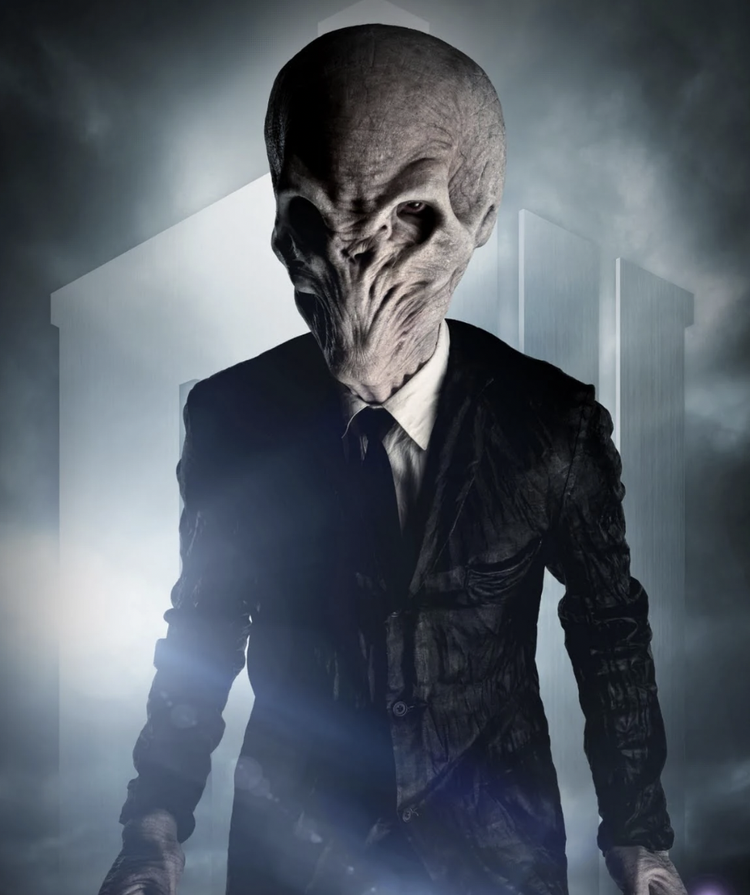

Kids would build those Daleks out of cardboard and bin lids again, not just download PNGs. They’ll be back in the art cupboard instead of scrolling through digital fan art. There was a bootleg t-shirt kicking around a fair while back of A Weeping Angel and one of The Silence in a “Staring Contest”. Brilliant. You can’t make that out of what they recently did with Omega.

That’s what made the Daleks, the Cybermen, the Sea Devils, and the Zygons iconic. Nobody’s dressing up as the “Skithra Queen” or the “Timeless Child” to go trick-or-treating.

See, it’s not just for the kids. Adults need a jolt too. When you can sense a creature’s weight, when you hear it scrape across the floor or see the light bounce off an actual, physical surface, you lean in. The uncanny valley is replaced with genuine discomfort—the right kind. The kind that used to make people hide behind the sofa, not hide behind their phones. At the very least, even semi-interested adults will appreciate the work that went into it.

If the BBC gave a damn about legacy, they’d realise that rubber lasts longer than code. The best stories live forever because people carry them forward, not because they were the biggest digital render of the year. Daleks survive because people want to be them, or beat them, or get terrified by them—not because they won a BAFTA for “Outstanding CGI Smoke.”

The unholy truth is that Nobody Cares.

This is bigger than Doctor Who. Look at Star Wars: when the sequels relied too much on digital effects, people shrugged. When The Mandalorian brought out a puppet Baby Yoda, the world lost its mind. The lesson? Give people something they can touch (or wish they could).

PUTTING THE SOUL BACK IN THE SHOW

Here’s a radical idea. Don’t just bring in the monster makers, give them a seat at the writers’ table. Let the creature designers collaborate with writers so that monsters aren’t just a plot hurdle, but the emotional engine of the episode. This isn’t about making ‘cool stuff’—it’s about making stuff that means something.

Imagine a modern Who season where every major creature was built practically, with a story arc to match. Imagine giving the actors weeks of rehearsal with the monster team—letting stories grow organically from what the suits, prosthetics, and puppetry allow. Suddenly, you’re writing stories that fit the monsters, not shoehorning them in for a one-episode wonder.

You’d get performances with actual energy. Directors and DPs could do creative things with shadows, silhouettes, and practical gore or weirdness. The energy on set would change, and it would show up on screen.

And here’s a small side-benefit: jobs. Actual creative jobs in the UK, for artists, sculptors, puppeteers, and physical FX people. The show that almost single-handedly built the British TV industry could help revive it for the next generation, instead of just farming out VFX to whoever’s got the lowest bid–and I dread to think that somebody at the BBC is hitting Fiverr to find them.

THE MONSTER GOSPEL: REAL > VIRTUAL

There’s a gospel truth that Doctor Who—and, let’s be honest, most of the modern TV industry—needs to hear:

If it isn’t real, it isn’t scary. If it isn’t scary, it isn’t memorable. If it isn’t memorable, it isn’t worth the trouble. We will all wander off into the archives of a streaming service to find something that is.

When you build a monster in the real world, it leaves footprints. In the set dust, in the memories of kids, and in the photos that’ll be circulating at conventions for decades. Hell, think of the documentaries you could get out of it and university courses even! It doesn’t matter if the zips show or the eyes go a bit wobbly. That’s charm. That’s what makes something alive. The audience will forgive the odd flub if you treat them to a sense of wonder, and they’ll cherish the show for it.

Stop apologising for being a little bit homemade. That’s Doctor Who’s birthright. The show was never meant to be slick. It was meant to be imaginative and to be educational about the world (real or otherwise), but when was the last time the Doctor visited Ancient Greece?

As Guillermo del Toro once said, “The beauty of a monster is in its flaws.” Let Who be weird, wonky and brilliant again.

THE CHALLENGE TO THE BBC: GROW A SPINE

So, BBC: here’s your challenge.

Tear up the green screen contract. Put away the rendering farm. Call up the people who made The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, or the UK’s own Millennium FX (who worked on earlier seasons of Who if you didn’t fall out with them). Let them make a mess. Let them fill your studios with foam, latex, and paint fumes until the accountants faint.

Spend your money on sweat, not software. Give us something to believe in, even if it looks a little dodgy under the lights—that’s part of the magic. Let us see the monsters’ breath on a cold studio set. Give us a reason to care again. If you do, you’ll give the world a Doctor Who that people will actually miss when it’s gone. I know there’s budget available—Gary Lineker’s not using it now he’s hung up his gloves.

If you must use CGI, use it for what it’s good at: lasers, backgrounds, swirling time vortexes, and the odd spaceship exterior. Leave the monsters to the professionals—the ones who still know how to glue something horrifying together with their own hands.

Doctor Who can be legendary again. It can be the show everyone wants to copy, not the one desperately copying everyone else. But it takes nerve, and it takes a willingness to get weird again.

Nobody ever had nightmares about a green screen. But the right monster—real, heavy, slightly sweaty under the studio lights—will live with you forever.

Bring back the monsters.

That’s how you fix Doctor Who.

Everything else is just noise.

One more time: BBC, I love that you exist but you have the opportunity to lead here. Are you bold enough?

Footnote: If you want to cast a Doctor that nobody can argue with and ticks an awful lot of boxes, give Joanna Lumley a call.